By Connor Scholes and John Evans –

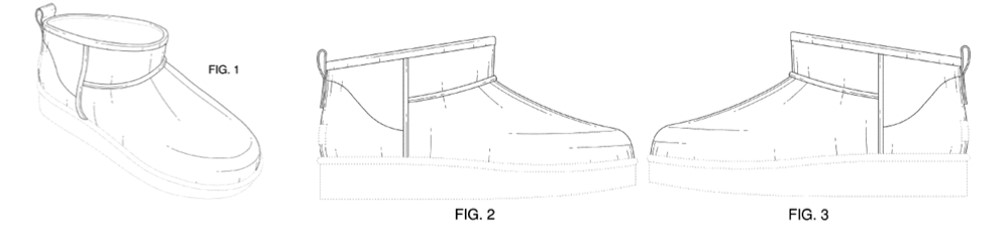

In a recent decision, the PTAB determined that images of products offered for sale via online retailers, such as Amazon, did not alone qualify as printed publications—even if the images showed the product and the date it was offered for sale. Next Step Group, Inc. v. Deckers Outdoor Corp., IPR2024-00525, Paper 16 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 6, 2024) (“Decision”). Here, Next Step Group, Inc. (“NSG” or “Petitioner”) requested IPR of U.S. Patent No. D927,161 (“the ’161 Patent”), titled “Footwear Upper.” The ’161 Patent relates to an ornamental design for footwear, as shown below:

In their IPR petition, NSG asserted ten grounds of invalidity. NSG relied on screenshots of Deckers’ (and competitors’) footwear offered for sale online through Amazon and other retailers. The PTAB evaluated whether these references qualified as “printed publications” prior art for the purposes of establishing unpatentability. Ultimately, the PTAB found that NSG had not shown they were printed publications, and had not shown a likelihood of success in proving unpatentability of the ’161 Patent. Thus, the PTAB denied NSG’s petition.

In an IPR, a petitioner may request cancellation of claims “only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. § 311(b). The petitioner bears the burden of establishing that a reference “was publicly accessible before the critical date of the challenged patent, and therefore that there is a reasonable likelihood that it qualifies as a printed publication.” Decision at 10 (quoting Hulu, LLC v. Sound View Innovations, LLC, IPR2018-01039, Paper 29 at 16 (PTAB Dec. 20, 2019) (precedential)). This is a case-specific inquiry, which requires analysis into the circumstances of the reference’s disclosure to the public. “The key inquiry,” the PTAB explained, “is whether the reference was made ‘sufficiently accessible to the public interested in the art.’” Decision at 10-11 (quoting In re Lister, 583 F.3d 1307, 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2009). For webpages, this requires a showing that a person of ordinary skill could have found the website and specific reference: “It is not enough that a webpage simply existed on the critical date.” Id. In this case, the critical date was the effective filing date of the ’161 Patent, which was November 8, 2019.

While NSG asserted several references in attempt to show the claimed design was used in products offered for sale before the critical date, many were not appropriate printed publications. Screenshots of the “UGG® Neumel Boot” that NSG presented were not printed publications; even though the screenshots suggested that the boots first went on sale in 2015, there was no additional evidence to show that the public had access to them on that date. Decision at 14. For example, while the screenshots show Amazon customer reviews of the product, none of the reviews dated prior to the critical date contain any images of the product.

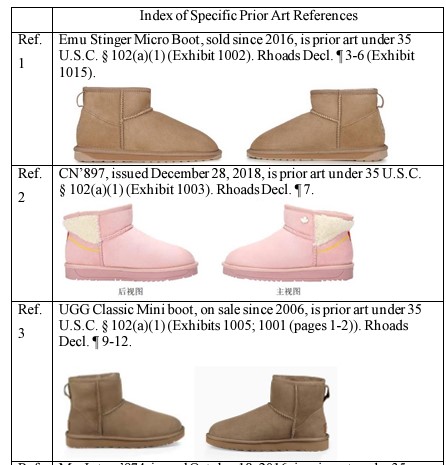

Another asserted reference contained images of a different boot, the “Emu Stinger Micro Boot” (sold by Deckers’ competitor). NSG similarly argued that screenshots and images, showing this product offered for sale, and were printed publications. The PTAB here noted that “webpages are dynamic; product listings may be updated; and photographs of the products on the website may change over time. As such, a print out of a webpage from 2024 does not provide sufficient evidence of what was publicly available on the website years earlier prior to the critical date.” Decision at 18. The screenshots were produced in January 2024, which does not show that “the images displayed on the website in 2024 were publicly available prior to the critical date.” Decision at 18 (emphasis in original). Further, images of the boot differed from one page to the next, and the images in one exhibit displayed two different websites.

Similar screenshots of a third boot—the “UGG® Classic Mini”—met the same fate. Here, the cited images contained only one side-view of the boot, with a copyright date of 2024. While 3 pages of the exhibit were dated 2015 (which the PTAB noted as providing “some indicia of reliability that these pages were printed and publicly available before the critical date”), other pages bore a date from 2020, after the critical date. Further, the images contained in the exhibit “are remarkably so poor that this prior art also cannot be considered fairly represented for design patent prosecution.” Decision at 23.

Finding that NSG had failed to meet its burden that the images of boots offered for sale were printed publication prior art, the PTAB construed the challenged claim and evaluated Petitioner’s grounds of unpatentability. Ultimately, the PTAB declined to institute IPR on the asserted grounds, noting that many of the references NSG had relied upon did not qualify as prior art. In some cases, the PTAB found that, even if the references had been qualified, they would not be sufficient to warrant institution of IPR. Thus, institution was denied.

Takeaway: When using websites as prior art, a petitioner must do more than just show that the website depicts alleged prior art subject matter. Rather, the petitioner must also put forward evidence that the website was reasonably accessible to skilled artisans at the relevant time. While posted dates may provide some indicia of reliability, petitioners should take care to ensure that their references are consistent—showing different dates, different websites, or different pictures or products may ultimately harm a petitioner’s argument that their reference is printed publication prior art.

Latest posts by John Evans, Ph.D. (see all)

- PTAB Issues First Post-LKQ Design Patent Decision - September 27, 2024

- Petitioners Beware: Screenshots Showing Product May Not Qualify as Printed Publication - September 18, 2024

- En Banc Federal Circuit Overrules Rosen-Durling Test for Design Patent Obviousness - May 23, 2024