By: Jaime Choi, Tracy Stitt, and John Evans

On February 1, the PTAB held its first “Boardside Chat” of 2018, which featured three judges discussing appeals and AIA trial proceedings for design patents. Not only are such proceedings less common for design patents than for their utility counterparts, but they also invoke some different statutes, case law, and standards that may seem foreign to those who are more used to working with utility patents.

Perhaps the most conspicuous difference is the subject matter. Design patents are governed by 35 U.S.C. § 171, which provides that only a “new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture” is patentable. Thus, while their utility counterparts must be “new and useful” pursuant to § 101, pure functionality is a bar to design patent protection under § 171. Aside from subject matter, designs are subject to the same statutory requirements as utility patents—novelty (§ 102), non-obviousness (§ 103), and even written description (§ 112). But how those statutes are applied to designs is much different.

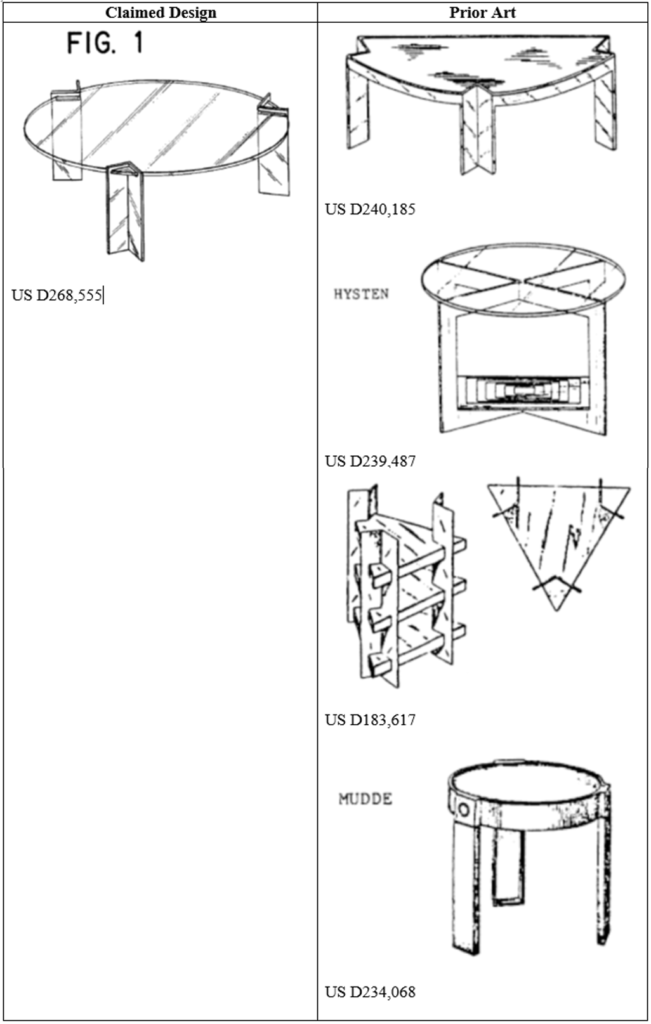

For example, the PTAB’s chat detailed the obviousness standard for design patents established by In re Rosen (673 F.2d 388 (CCPA 1982)), which is significantly different than the obviousness standard for utility patents. In Rosen, the CCPA (the Federal Circuit’s predecessor) overturned a USPTO rejection of the table design shown on the left, in view of the prior art shown on the right:

In evaluating the obviousness rejection, the CCPA applied what was at the time a new standard – whether the design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill of the articles involved – now referred to as the “ordinary designer” standard. Additionally, the CCPA established that a primary prior art reference in an obviousness analysis must have “basically the same” design characteristics as the claimed design. As such, under current CCPA and Federal Circuit law, a design cannot be rendered obvious by picking and choosing elements from prior art references, as sometimes can be done for utility patents. In Rosen, none of the prior art had basically the same design characteristics as the claimed design; indeed, modifying D240,185 to achieve the claimed table design would “destroy fundamental characteristics” of its design.

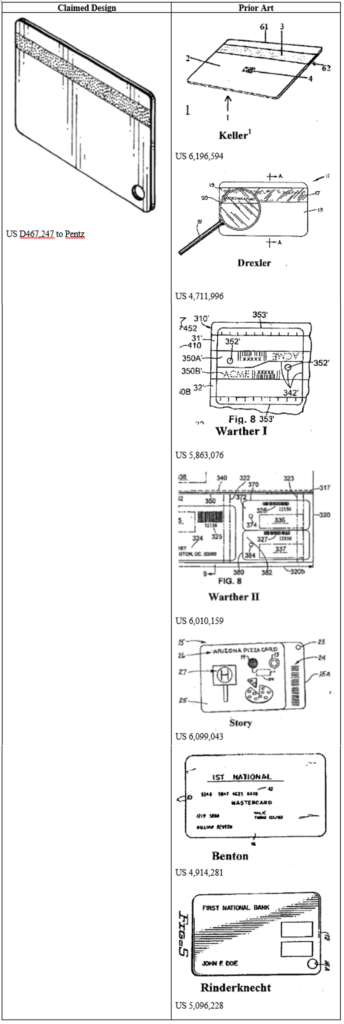

The PTAB also explained some cases where they or the Federal Circuit evaluated whether the primary prior art reference had the right design characteristics to qualify as a primary, or “Rosen reference.” One example was an inter partes reexamination of D467,247 to Pentz (BPAI July 31, 2009, 2009-002973) where the claimed data card design (on the left) was nonobvious because the prior art (on the right, of which Keller and Drexler were proposed as primary references) did not illustrate a data card with both a magnetic strip and an aperture, so there was no proper Rosen reference:

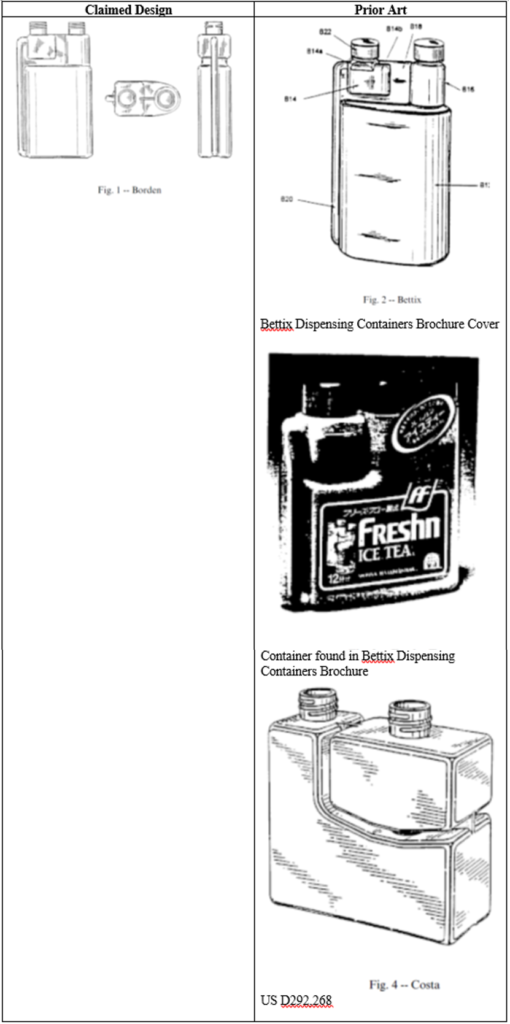

This is not to say the PTAB always finds that designs are nonobvious. The PTAB also discussed In re Borden, 90 F.3d 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1996), which involved the following twin neck dispensing container design (on the left) that was obvious in view of the prior art (on the right, of which Bettix was a proper Rosen reference):

The Federal Circuit identified similarities between the claimed design and the Rosen reference (Bettix) including an oval-shaped main chamber with a cylindrical spout, a small measuring chamber suspended by a thin laminate above the main chamber and adjacent to the cylindrical spout, and a filling tube running along the spine of the container and connecting the two chambers. The Federal Circuit found differences in the shape of the small chambers of the two designs, but that such features were in Fresh’n Tea and Costa and properly could be combined with Bettix.

Another key aspect of the PTAB’s chat was their discussion of the “ordinary designer” standard and the value added by experts in that regard. The PTAB noted that in the few design IPRs and PGRs that they have handled, very few have included expert declarations. Such expert declarations have been crucial evidence time and again in PTAB proceedings for utility patents. The PTAB recommended that practitioners introduce expert testimony as to the qualifications and abilities of an “ordinary designer” for a particular design, and what would be that ordinary designer’s view of the obviousness, or nonobviousness of a claimed design.

Additionally, the PTAB noted that the vast majority of the invalidity theories considered involved obviousness, with anticipation arising only rarely, and functionality under § 171 even more rarely. The PTAB advised that practitioners wishing to invalidate a design patent as obvious (e.g., in an IPR or PGR) may consider presenting detailed arguments as to why the primary reference is proper under the Rosen standard, e.g., to specifically explain each possible similarity between the claimed design and the primary reference, both as a whole and on a feature-by-feature level. Conversely, practitioners wishing to avoid a finding of obviousness may consider elaborately explaining all of the differences between the claimed design and the primary reference to support an argument that there is no proper Rosen reference.

Other Boardside Chats are posted online, and address subjects ranging from evidence to PTAB statistics.

Latest posts by John Evans, Ph.D. (see all)

- Show Me the Evidence: Primary References Still Required after LKQ - October 3, 2025

- Another Fender-Bender between LKQ and GM - July 31, 2025

- PTAB Issues First Post-LKQ Design Patent Decision - September 27, 2024